This month has been riddled with challenging airway situations, so I thought it would be a great opportunity to discuss how I perform awake fiberoptic intubations. The decision to intubate someone awake is rooted in the high likelihood that the patient will be a “difficult airway” for whatever reason. Keeping the patient spontaneously breathing will ensure that if the airway cannot be secured, oxygenation and ventilation can be sustained for the time being.

Before anything, I begin with a focused history and airway exam. Will a limited neck range of motion or trismus limit my ability to intubate orally? Will I be faced with significant bleeding in a coagulopathic patient requiring a nasal intubation? What other comorbidities must I consider regarding the induction of anesthesia once the intubation is completed? Above all else, how can I keep the patient calm and cooperative during the entire process?

In elective awake fiberoptic intubations, I’ll explain the process to the patient, reassure them that this procedure is in the interest of safety, and explain how I’ll reiterate the steps once we actually start. I’ll also mention that our surgical colleagues will often be present to establish a tracheostomy if there’s an emergency.

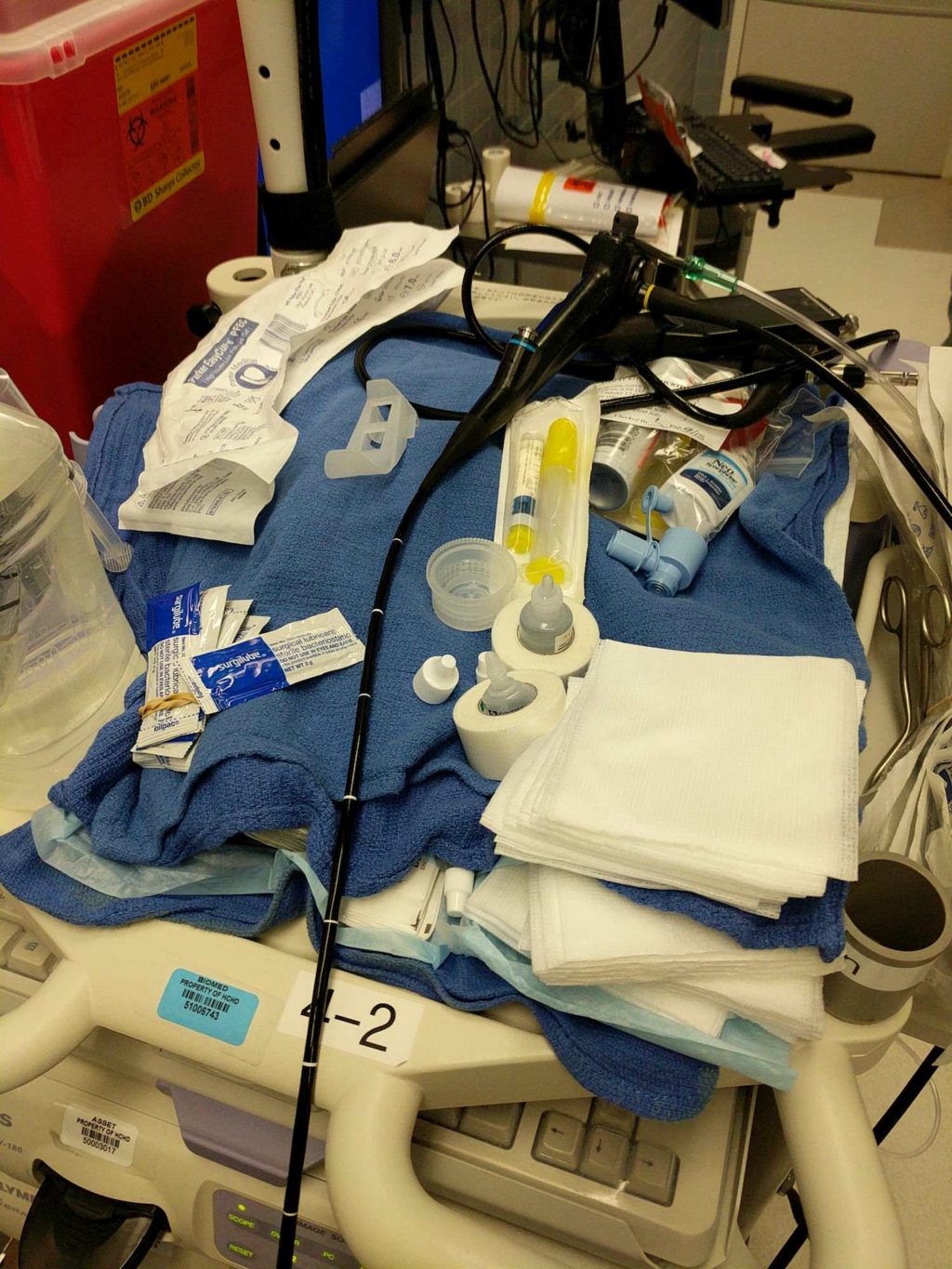

Here are my steps to performing an elective, awake fiberoptic intubation:

- 0.2 mg of IV glycopyrrolate to dry the mucous membranes and promote better adherence of local anesthetic. I’ll warn the patient that they might feel like their heart is racing. I’ll occasionally give 4 mg of IV ondansetron for nausea prophylaxis as well.

- Sit the patient up. Apply the standard monitors – pulse oximeter, EKG, and blood pressure cuff.

- Place a nasal cannula. This will provide extra oxygen during instrumentation.

- If I’m doing an oral intubation, I’ll apply lidocaine jelly to the tongue with a tongue depressor and have the patient gargle lidocaine spray. For a nasal intubation, I’ll coat nasal trumpets with lidocaine jelly, spray decongestant (oxymetazoline or neo-synephrine) into both nares, and serially dilate one of them to a size larger than the endotracheal tube I’ll be using (6.0 for women, 7.0 for men). During this process, I’m also preoxygenating the patient with a facemask and only intermittently removing it to exchange nasal trumpets. I leave each one in for ~30 seconds.

- For oral intubations, I’ll thread the endotracheal tube (ETT) on the bronchoscope and slowly advance into the oropharynx. For nasal, I’ll coat the ETT in lidocaine jelly, advance it several centimeters into the naris I previously dilated, and then advance the bronchoscope through the ETT. I’ll have an assistant place lidocaine in-line so I can spray it above and below the vocal cords in both oral and nasal intubations. This “spray-and-go” technique almost invariably has the patient cough once or twice.

- Once the bronchoscope is in the trachea, I’ll gently rotate the ETT off, confirm its position 2-3 centimeters above the tracheal carina, and remove the bronchoscope. I’ll confirm we have adequate ventilation, and then induce with a combination of volatile gas (usually sevoflurane) and propofol.

Some practitioners provide dexmedetomidine or ketamine sedation since both of these medications preserve the respiratory drive and provide some degree of analgesia. Others will begin lidocaine topicalization with a nebulizer for several minutes prior to airway instrumentation. I’ve found that as long as we dry the mucous membranes, topicalize very well with lidocaine jelly and spray, and perform the “spray-and-go” technique, patients tolerate this procedure incredibly well.

Still have to perform my first one…. A post which made only eager to do so