It’s always interesting to see how practitioners interpret the utility of lactate. Some find it completely useless, others think it’s a marker of poor oxygen delivery, and a decent number trend lactates as a way to measure the response to therapy. So let me briefly discuss my views on lactate during a critical illness like sepsis.

The notion that lactate is ALWAYS the byproduct of anaerobic metabolism due to poor oxygen delivery isn’t true. Sepsis is often characterized by a hyperdynamic circulation with tissues receiving plenty of oxygen. If tissue dysfunction were truly from a lack of oxygen, we would see a lot more necrotic tissue (not a buzzword we routinely associate with sepsis).

Although I agree that a (very high) lactate parallels disease severity, it’s also an important fuel used by vital organs like the brain and heart during times of stress. In addition, several studies have shown the negative effects of stifling lactate production and, similarly, the benefits of providing supplementary sodium lactate (i.e., after cardiopulmonary bypass in patients with ischemic heart failure).

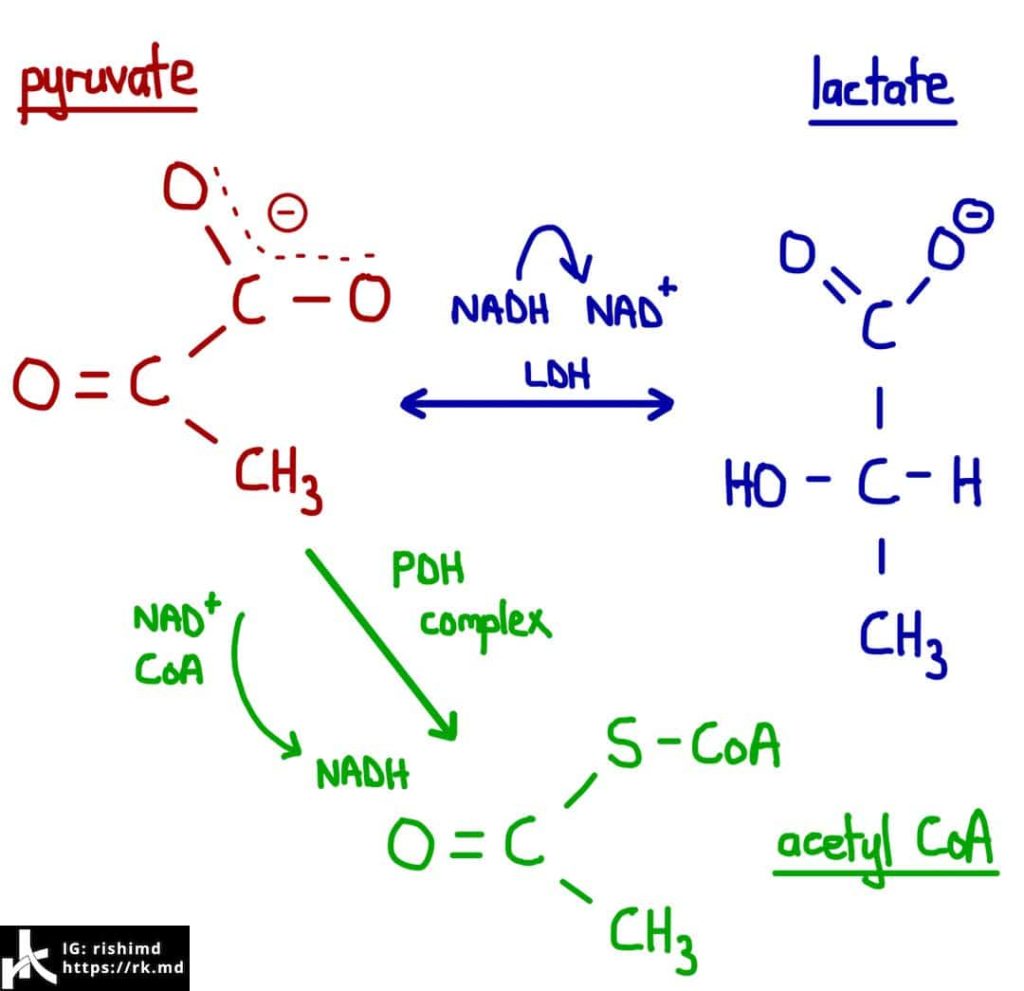

A catecholamine surge from the stress response and/or vasoactive infusions contribute to beta-2 adrenergic receptor activation which ramps up glycolysis and creates a surplus of pyruvate that cannot enter the TCA (“Kreb’s cycle”) as acetyl CoA substrates. Instead, the excess pyruvate substrate is shunted into the lactic acid pathway via lactate dehydrogenase (LDH). Yes, this even occurs during AEROBIC metabolism. This is why patients who are clinically improving on vasoactive infusions might maintain higher lactate levels!

This is also why a patient who appears compensated (think of your young, otherwise healthy patients) worries me when their lactate is significantly elevated. The reassuring symptomatology is heavily catecholamine-dependent, and although they appear well, decompensation could occur at any point.

Lactate is an important fuel and normal physiologic response to catecholamine-rich states. However, if you’re going to use it as a surrogate for disease resolution, interpret the trends carefully and be mindful of confounders.

How do you use lactate in diagnosis and guiding response to therapy? Drop me a comment below!

What is your thought about what fluid bolus protocol to initiate? Some of the ed providers I work with follow the 30 mg/kg and some do just a liter depending on if lactate is > or < 2.0…. and in the heart failure patient who already has increased BNP how do you formulate proper bolus protocol ? Thanks

Such a great question, Nolan! I too have seen this tendency to bolus the heck out of patients coming in with signs of sepsis. Many of the original studies (ie, early goal directed therapy) incorporate fluid boluses with objective measurements of intravascular volume resuscitation (like CVP). Don’t get me started on the uselessness of CVP (yes, even the trends). 😀

More recent studies dealing with enhanced recovery protocols have shown how detrimental IV fluids can be, especially with regards to maintaining the integrity of our glycocalyx. To me, lactates that are that low don’t give me a great reason, alone, to administer fluids. I’ve become a fan of other tests: leg raise, echo of the heart and IVC, pulse pressure variation in intubated/paralyzed patients, etc. Based on these tests, I’ll tailor my fluids accordingly.

Assessing volume status is one of the most underrated aspects of acute care medicine, and I think people will still do whatever they’re more comfortable with. 🙂