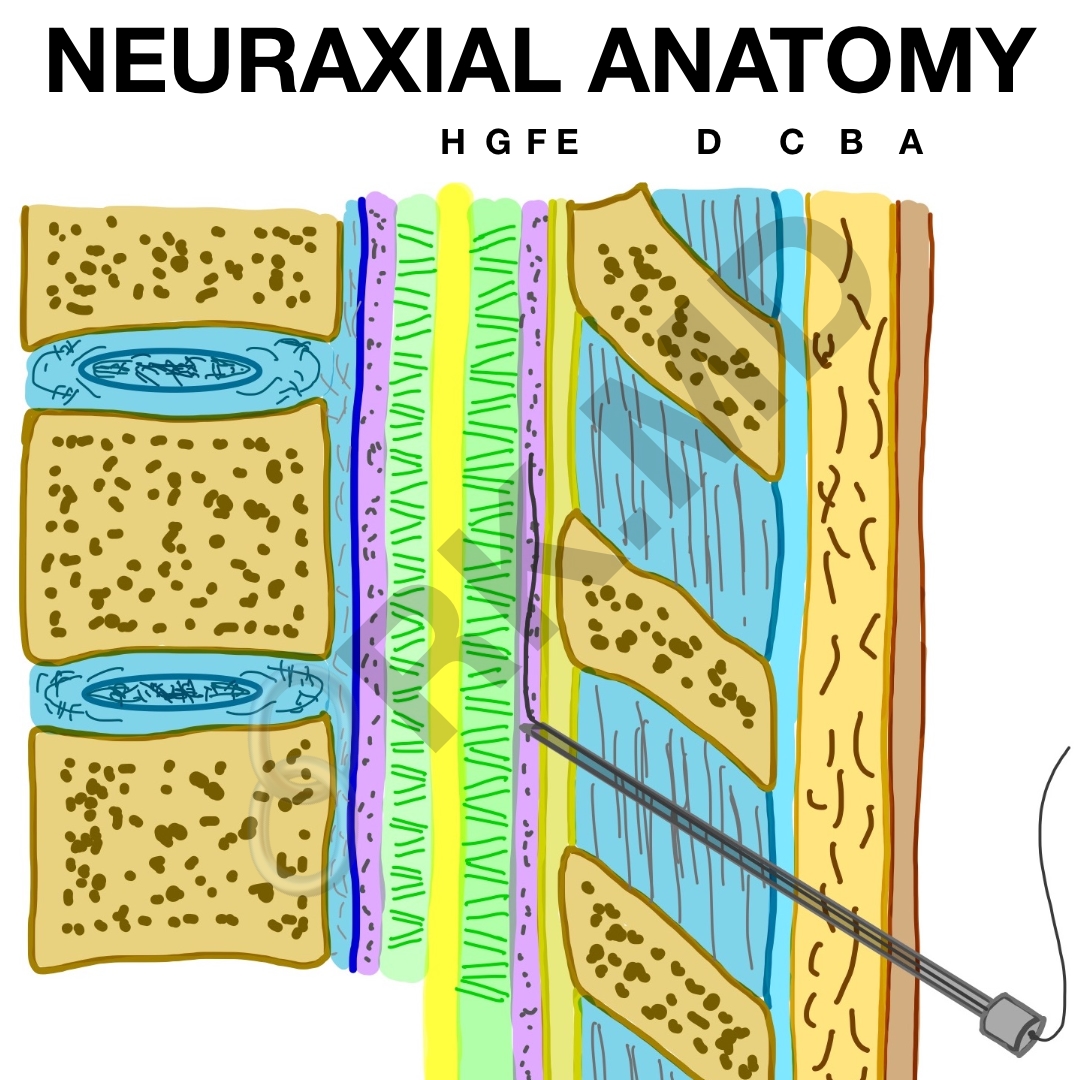

Understanding neuraxial anatomy is an essential part to successfully perform epidural and spinal (intrathecal) anesthetics. Here’s a schematic outlining the layers we encounter when performing these procedures:

- A: skin

- B: subcutaneous tissue

- C: supraspinous ligament

- D: interspinous ligament

- E: ligamentum flavum

- F: epidural space

- G: subarachnoid space

- H: spinal cord

First, we must determine if a patient has any contraindications for neuraxial anesthesia:

- Patient refusal

- Infection near needle insertion site

- Uncorrected coagulopathy

- Hypovolemia

- Elevated intracranial pressure (ICP)

Next, we need to consider the nature of the procedure. Spinal anesthetics are great for short duration lower abdominal, perineal, and lower extremity surgeries. They provide a great block but are fairly short-lived depending on the medications used. At the time of this writing, keep in mind that the FDA has only approved three medications for spinal (intrathecal use):

- Duramorph (preservative free morphine)

- Baclofen

- Ziconatide

Notice no local anesthetic on that list. That always amazed me. 😯

Epidurals, on the other hand, provide anesthesia/analgesia for extended periods of time via a catheter left in the epidural space; however the blockade isn’t as deep as a spinal. Another benefit is that epidurals can be placed virtually anywhere along the spinal column whereas we avoid spinals above the lumbar region due to potential injury to the spinal cord itself. Remember in adults, the spinal cord terminates at ~L2.

In either case, we pass the skin → subcutaneous tissue → supraspinous ligament → interspinous ligament → ligamentum flavum → epidural space. For an epidural, we feel a “loss of resistance” to either air or saline. he epidural space is a potential space outside of the dura. By filling this space with medication (typically local anesthetic +/- a narcotic), we are able to provide analgesia/anesthesia by affecting spinal nerves that exit the cord.

For a spinal, we traverse through the epidural space, “pop” through the dura and arachnoid meningeal layers to enter the subarachnoid space. Whereas entry into the epidural space is by “feel”, we can confirm we are in the subarachnoid space by seeing cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) leak back. Because we directly bathe the spinal cord with medication, doses tend to be 10x lower than that of epidurals. Patient positioning and the baricity of the medication (typically dextrose-containing, hyperbaric local anesthetic) dictate which segments of the spinal cord will be anesthetized.

Hopefully this illustrates some of the basic differences between epidurals and spinals. Drop me a comment below with questions! 🙂

What are your thoughts about the refusal to use local anesthetics for spinal anesthesia? It has surprised me, because we always used local anesthetic for this purpose.

You mean why the FDA hasn’t approved local anesthetics for intrathecal administration? Beats me! I think the general consensus is that they are safe to use. 🙂

what drug instead of local anesthetic ? despit some additive perhaps having anesthetic effect such as meperidine currently there is no alternative