Throughout my training as a cardiothoracic anesthesiologist and intensivist, I’ve worked hand-in-hand with surgeons and circulating nurses in the operating room and ICU settings. We’ve seen patients make miraculous recoveries and others succumb to the natural course of their ailments. We’ve laughed together, had dinner together, consulted each other, and above all, learned from each other. In doing so, we’ve created a mutual respect and trust that extends beyond our respective practices.

However, from time-to-time, I hear horror stories from anesthesia residents about surgical trainees, attendings, and circulating nurses scolding them for slow turnover, taking too long for procedures, “light” anesthesia, unstable hemodynamics, and a myriad of other complaints. Although some of my surgical colleagues rotate through the anesthesiology service during their residencies, many of them do not and are therefore completely unaware of what goes on “behind the curtain.”

I’ve been fortunate to work with wonderful perioperative physicians and nurses over the years, but since this is a public post, let me discuss some things that I wish all surgeons and circulating nurses knew about anesthesiology.

- Patient safety above all else. I don’t care who you are, where you trained, or what you’re doing at the moment – if I’m worried about our patient’s safety, then I will speak up. Under general anesthesia, they cannot defend themselves, so I will no matter how ignorant or annoying it makes me look.

- Induction and emergence from general anesthesia can present hemodynamic and airway challenges. This isn’t the time to start gossiping or discussing your evening dinner plans while the anesthesia team “worries about it.” If you were a patient emerging from anesthesia, would you want to hear five different social conversations in the background? Please offer a helping hand whenever possible and keep unnecessary discussion to a minimum during these potentially tenuous moments.

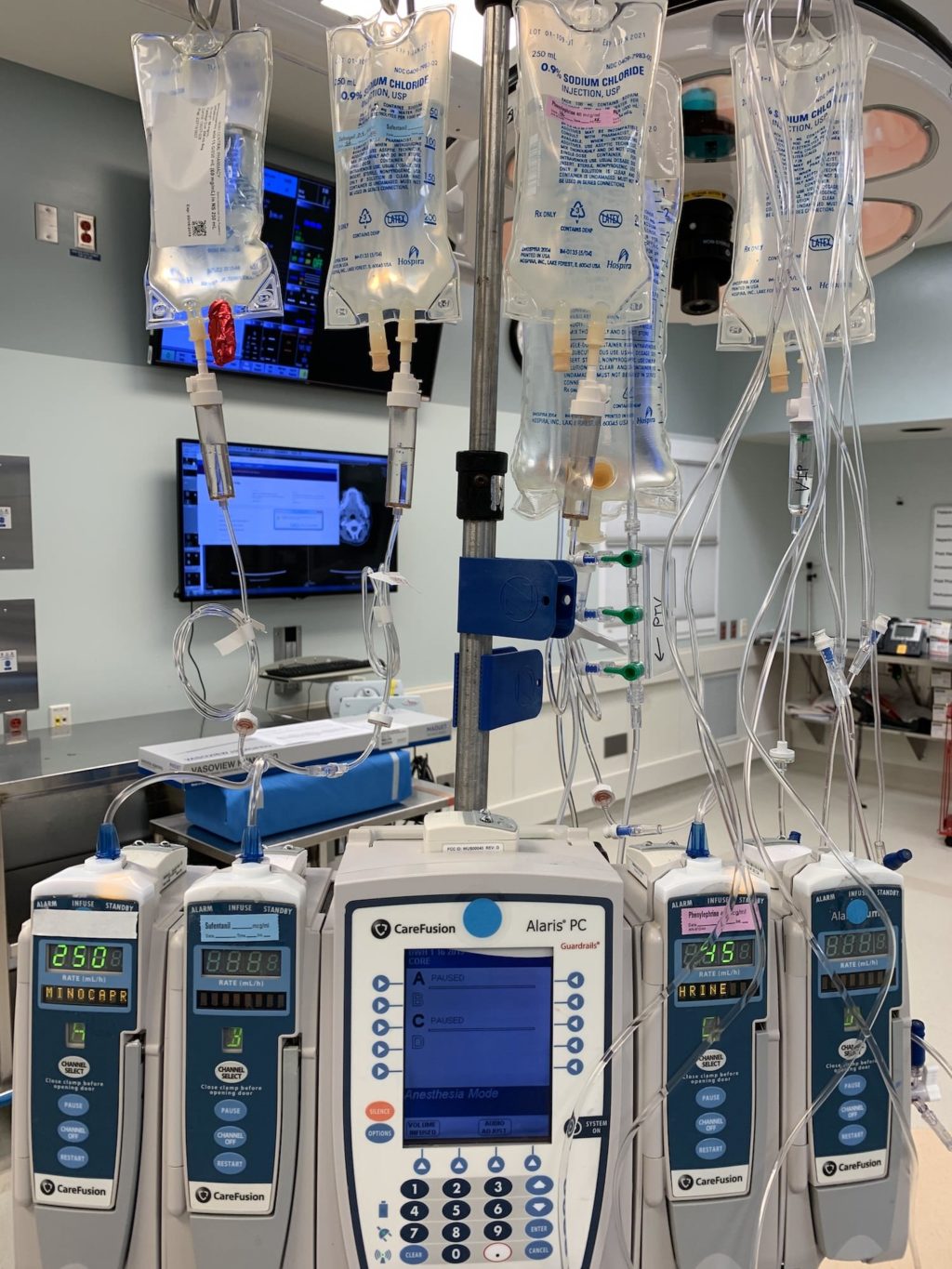

- Hemodynamics aren’t on a knob. I understand that you want the blood pressure and heart rate controlled, but trust that I’ve been watching the vital signs even more than you and am working on a differential diagnosis and potential interventions.

- Just like your instruments, not all of our medications and monitors are readily available to us at all times. Be patient. We will get that special antibiotic, blood product, etc. in due time.

- Our procedures sometimes take more time than expected, but we’re always pushing ourselves to be as fast as (safely) possible. If it takes 30 minutes to do an arterial line or thoracic epidural, it’s not because I’m slacking or incompetent. Some patients just present a technical challenge! By the same token, when you inadvertently nick the aorta or spend four hours doing a MitraClip, I understand. Respect for each other’s time goes both ways.

- The operating room is a collegial environment filled with individuals from various backgrounds – physicians, nurses, PAs, perfusionists, etc. Listen to the input of ALL team members as you steer the ship. Some of the best surgeons I’ve worked with show incredible humility when they admit a lack of knowledge, ask for relevant input from others, and seek help! By the same token, I don’t tell you what instrument to use, so don’t dictate how I should be addressing lab values, urine output, the airway, etc. Let’s reach a consensus about what to do as a team!

- I’m not making the OR into a sauna to make you miserable in those gowns and under the lights. Temperature regulation is significantly altered during general anesthesia, and no matter how much we provide warm fluids and maintain respiratory heat/moisture, having body cavities open creates significant evaporative losses. The resulting hypothermia certainly isn’t going to help coagulopathy or wound infection rates. I’ll use sterile Bair Huggers, warming the room, and any other means to maintain our patient’s temperature.

- I don’t show up to work thinking “how am I going to please the surgeon today.” I’m there for the patient. If you think that I’m recommending a certain procedure or precautions to delay you or to play “CYA medicine”, then you’re sadly mistaken and I pity your inability to look at the big picture.

- Turnover is a multidisciplinary effort involving everyone from anesthesia and scrub technicians to nurses, patient care assistants, anesthesiologists, and housekeeping. I do everything I can to shift your additional cases into vacant rooms and prepare ahead of time, but sometimes this isn’t possible. Deal with it.

- Let’s be adults here – unless you want to be addressed as “surgeon” or “nurse”, I prefer to be called “Rishi” instead of “anesthesia”… especially if I’ve taken the time to introduce myself.

Again, I’ve been very lucky to work with such collegial perioperative teams over the years. I have tremendous respect for surgeons, their training, their technical skill, and their dedication to patient care. Just as I try to facilitate their job, I want them to understand mine. 🙂

The CRNA asks us not to touch the patient who is emerging from general anesthesia. (It’s a selective surgery. No events. ) Why is that? He said the touching/the stimulation would cause him to lose the patient’s airway. My question is, if the tube is still in, you can still lose the airway? If the tube is removed and then the airway is lost afterwards, is it possible that it is because the tube is removed too early? I am just curious, I was not educated on this aspect at all. Thank you in advance.

Not really sure why. In the right patient population, there’s a chance of bronchospasm/laryngospasm after the endotracheal tube is removed. I do ask my colleagues to keep the noise down during emergence as patients can hear long before they “appear” awake.

Wouldn’t it be safer to wake up the patient after they are transferred off the table to avoid any unnecessary touching? When the patient is still on the table, there are often multiple people in the room who would start to pull off drapes, remove bovie pad, position the stretcher next to the table. This can require touching the patient to try to move the patient’s arm to the chest. which could increase the risk of airway obstruction or other complications during the emergence from anesthesia. Why this practice aren’t consistent, once a while, “Don’t touch the patient”.

There’s no way to standardize things like this – too many variables. Patients emerge at different rates, and there are situations where one would intentionally want to be extubated while still “deep” which go beyond the scope of this post.

Oh~~ Interesting! Thank you so much!

Typically, patients are extubated after being transferred from the operating table to the stretcher, with no one touching the patient once they are off the table, except when assistance is requested by the CRNA. However, in an elective surgery without any complications, under what circumstances where the patient needs to be brought to emergence and extubated on the table? This happened today, where the patient was extubated on the table. I remember the CRNA was requesting for an NG tube insertion around the time the surgical incision was being closed

You guys are always super busy. Your job is vital to the surgery we do. I think their are some people that you’ll never please. I’ve worked with surgeons who are great team players, and put the patient first, as it should be. And, some who don’t. The surgery goes much smoother when everyone works as a team, giving our patients 100%. I’ve been guilty of conversing at times; not proud of it. After a long weekend of call, working 16+ hours each day, doing back to back CABG’s, I get to that giddy phase. AND, it’s not fair to the patient, and the team. Thanks for pointing out where I can make improvements. Great post Rishi??????

Thanks so much for the comment, Sharon! 🙂